COLLECTION

The Museum owns the most complete and important collection of works by Costantino Nivola in the world, with over 200 sculptures and paintings acquired through donation over time. The initial collection given by Ruth Nivola, the artist’s widow, featured the sculptural work of Nivola’s final years, in particular his series of bronze and marble “mothers” and “widows”.

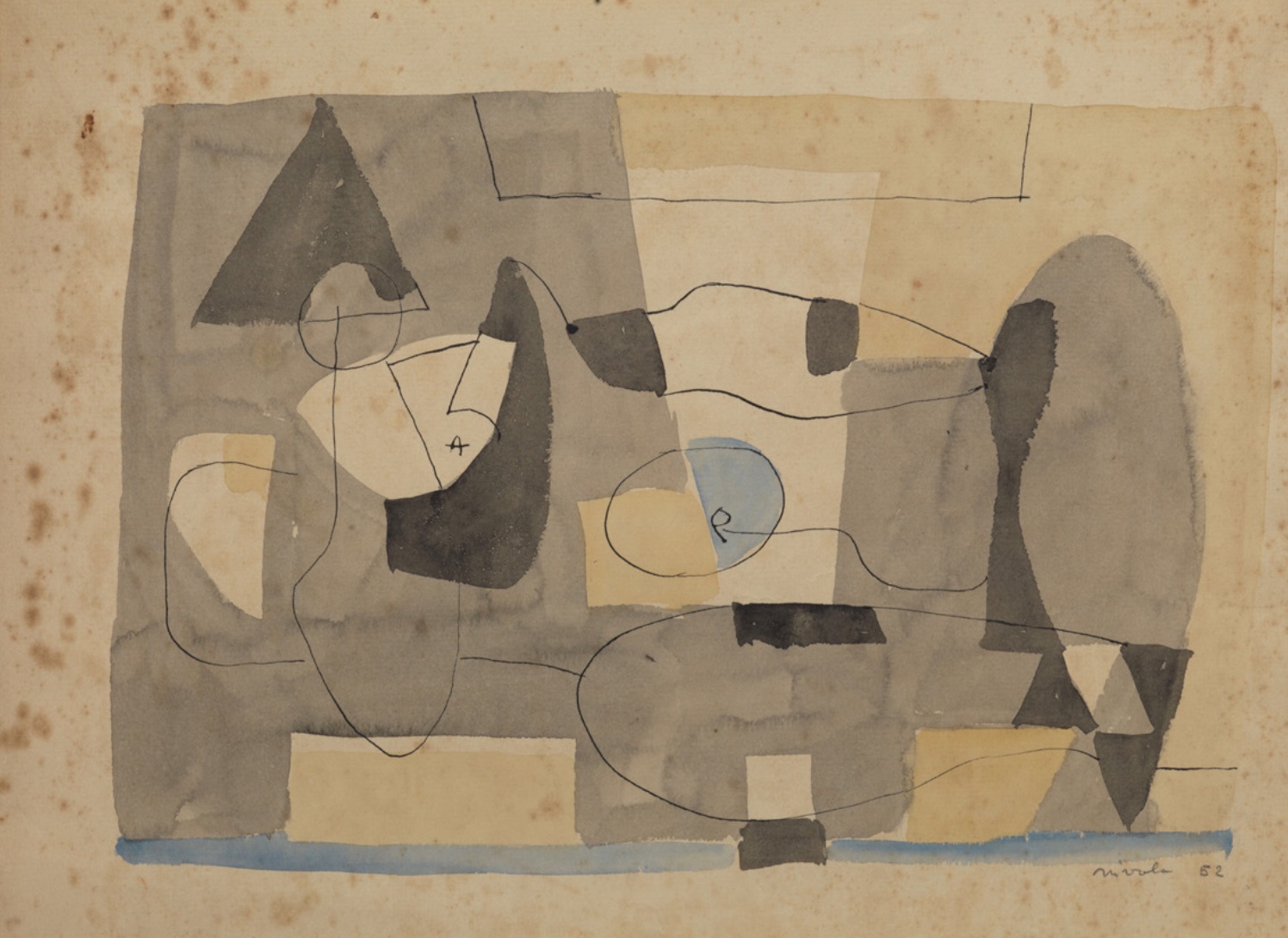

The collection grew to include smaller terra cotta works from the 1960s and 1970s (beds, beaches, swimming pools), several works in tin from the 1950s, a variety of paintings and models for public projects, and numerous sand cast bas-reliefs. The museum’s collection also includes a large number of Nivola’s works on paper, displayed in rotation.

Meeting Le Corbusier

The meeting with Le Corbusier in 1946 is for Nivola a defining moment in his artistic life. The cultural shock of exile and of relocation to a new environment had initiated in him a phase of disorientation. In America, contact with fellow European artists and architects who had emigrated to escape Nazi persecution, leads him to doubt his creativity. Le Corbusier puts an end to these uncertainties.

Nivola meets the master of modernism shortly after Le Corbusier’s arrival in New York as a member of an international team of architects in charge of the design of the new United Nations headquarters, and they begin a friendship destined to last until the death of the architect in 1965.

In free time left over from design sessions for the UN, Le Corbusier uses Nivola’s New York atelier to paint, and is often a guest at his house on Long Island. During this time, Le Corbusier introduces Nivola to modernist art, teaching him the fundamental principles of form.

The artist abandons his former figurative style, lively and elegant but still rather traditional, to begin a period of intense experimentation. Between 1947 and 1950 he produces paintings and a multitude of drawings inspired by post-Cubism, by Le Corbusier’s and Fernand Léger’s paintings, as well as by Surrealism. This period of exploration and research will soon bear fruit in Nivola’s first sculptural works.

The Olivetti showroom

In 1954, with the decoration of the Olivetti showroom on Fifth Avenue in midtown New York, Nivola begins his career as a “sculptor for architecture.”

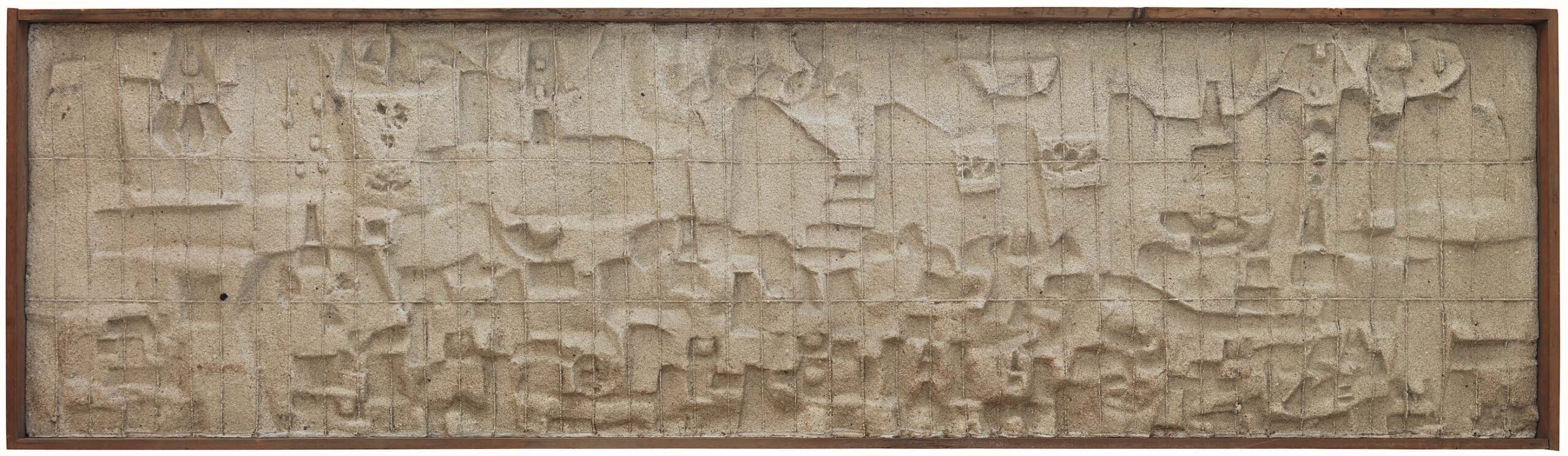

Designed by the Milan studio BBPR, the showroom is a place rich in imaginative, almost surrealist inventions: marble stalagmite-pedestals for the merchandise, stalactite-lamps in Murano glass, the large wheel of a paternoster connecting the street level showroom to the level below, and a typewriter placed on the sidewalk to entice passers-by. A perfect example of the “synthesis of the arts,” where architecture, sculpture and design come together harmoniously to general effect, the project has in Nivola’s work its most suggestive element. The relief, 23 meters long, is made with the sandcasting technique invented by the artist, (a plaster sculpture from a matrix modeled in sand), and represents a series of semi-abstract figures, divinities carrying in their laps small human figures who welcome visitors with ample gestures.

Visually detached from the sea-green floor and from the sky-blue ceiling as a strip of light, the “sand-wall”, with its grainy beach-like surface, lends a sense of lightness, and helps to evoke an image of the Mediterranean.

The great success of the project situates Nivola internationally as an ideal collaborator for modernist architects, while at the same time serving to affirm Italian creativity and design overseas. Dismantled in 1969 at the closure of the Olivetti showroom, the relief was relocated to the Science Center at Harvard University in 1973 on the initiative of the architect, Josep Lluís Sert.

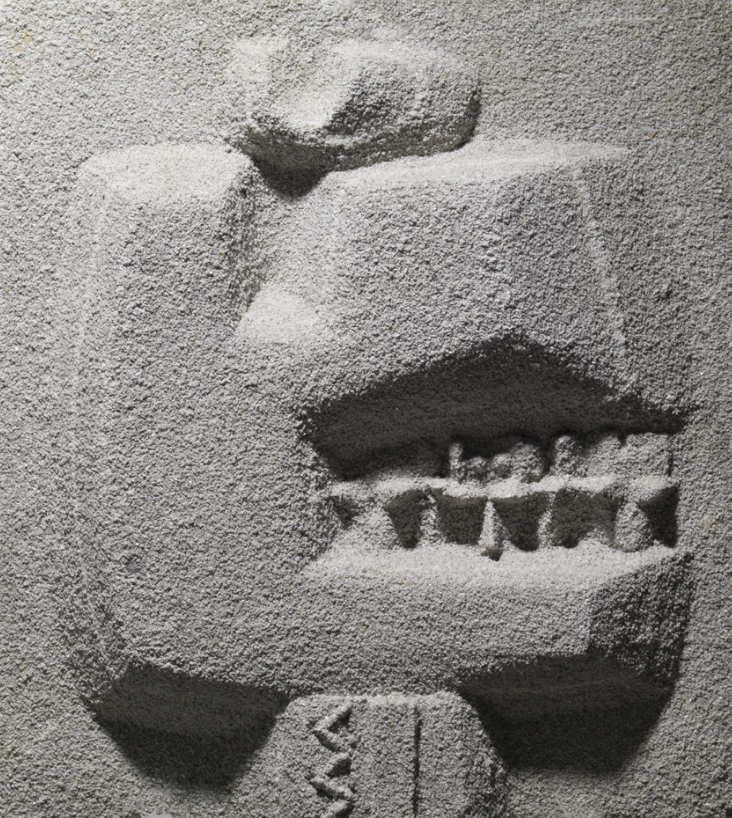

Sketch for the Olivetti showroom in New York, ca. 1953, sandcast, colored plaster, cm 74,4 x 70,2 x 6,5.

Photo P. Pinna

Graphic Design

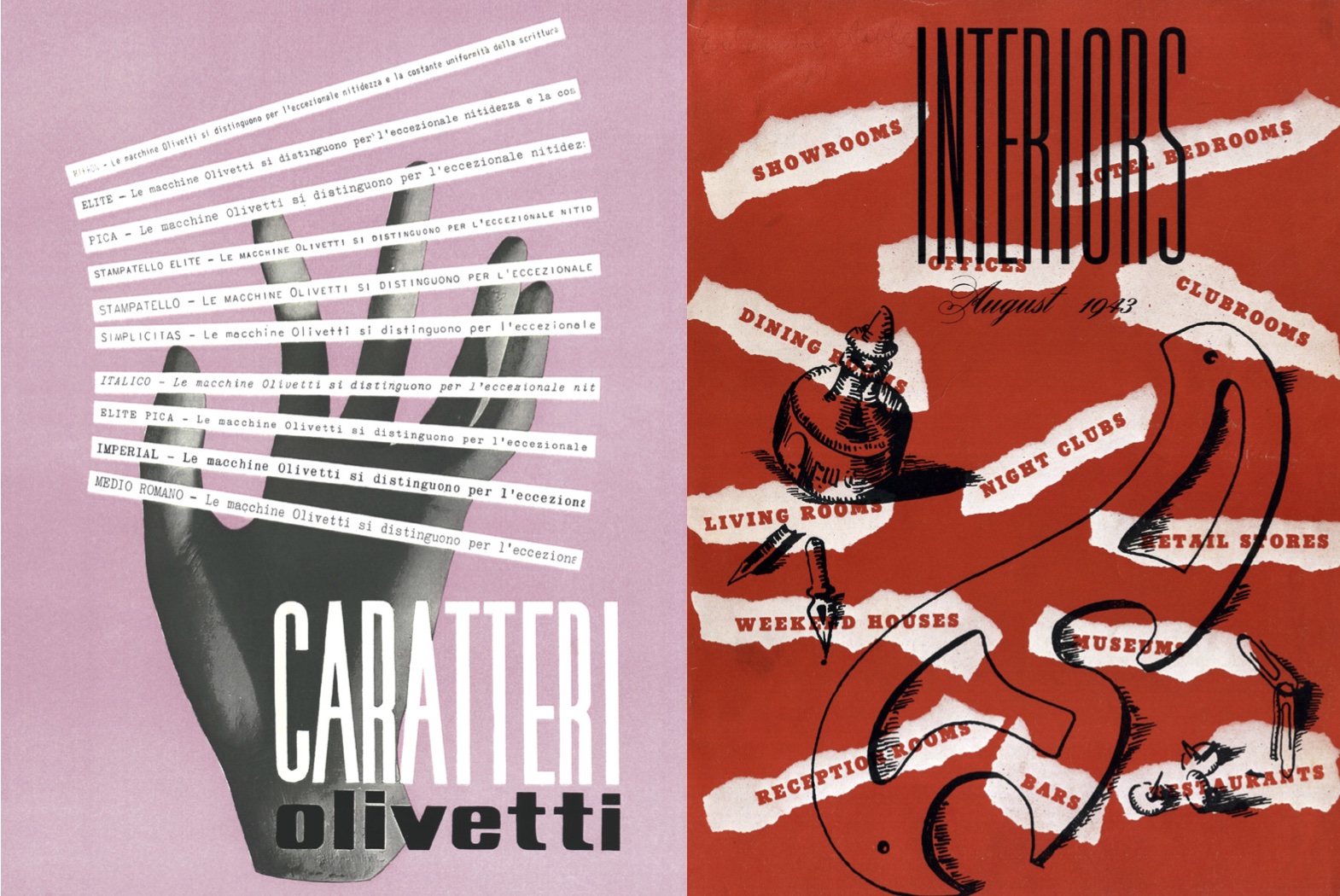

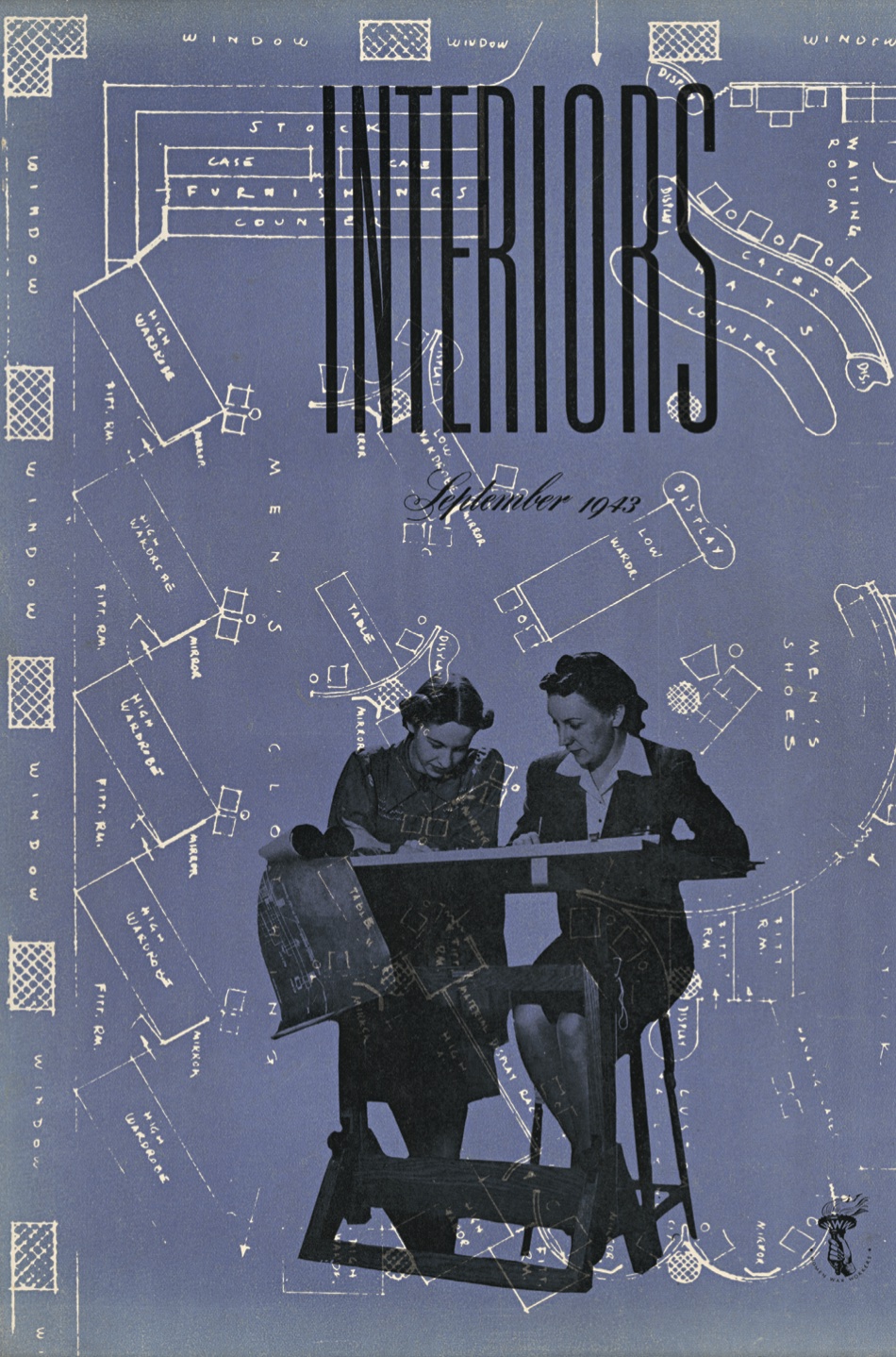

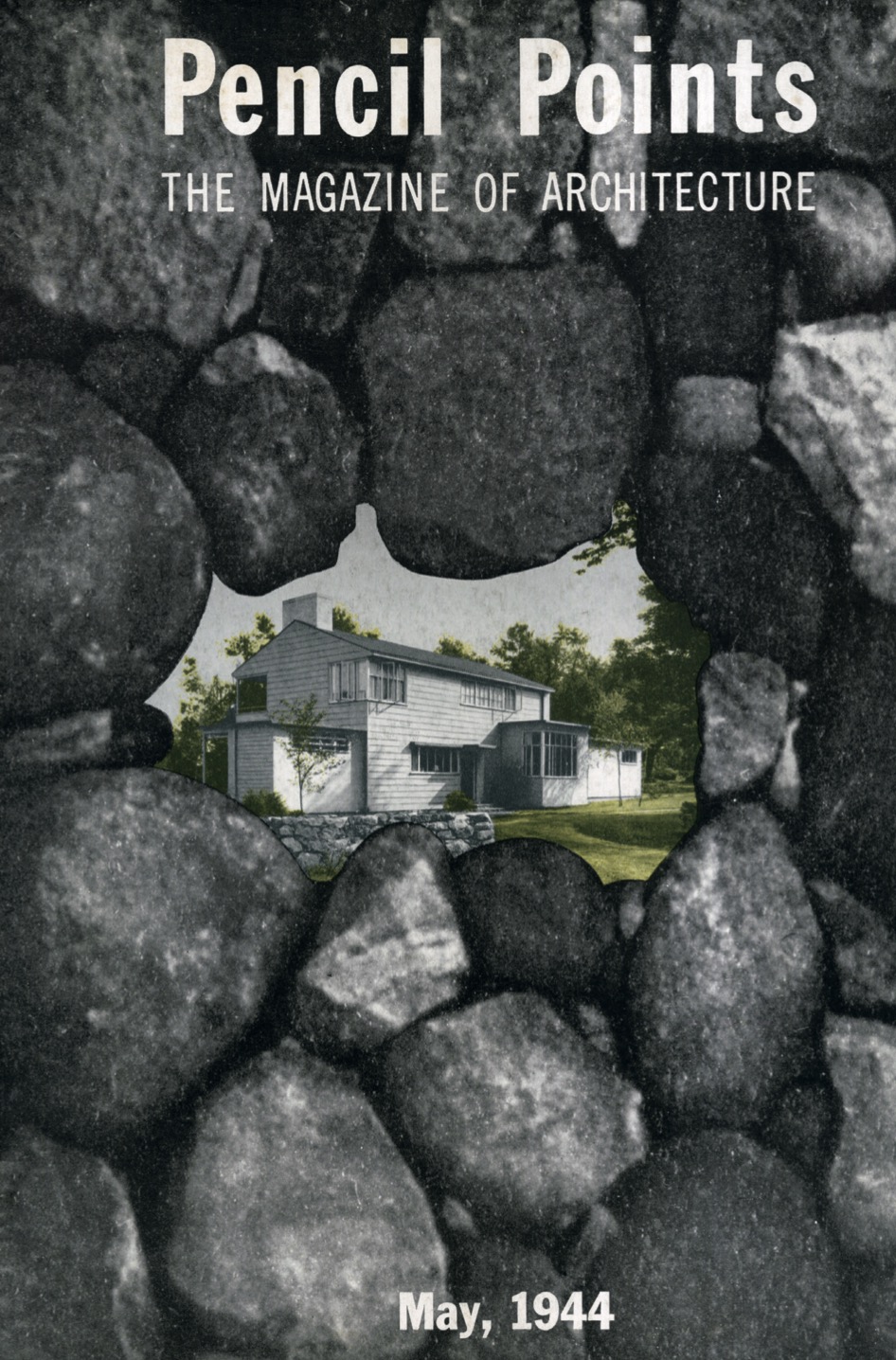

Nivola is today known mostly as a sculptor, but for over twenty years he was primarily a graphic designer and illustrator. After receiving his diploma at the ISIA of Monza, from 1936 to 1938 he works in Milan as an graphic designer for Olivetti, a company that, thanks to the foresight of Adriano Olivetti, plans its communication, product design and the architecture of its factories according to artistic criteria.

One of the first developers of the company image, together with Xanti Schawinsky and Giovanni Pintori, Nivola executes a number of posters and advertising campaigns highly innovative for that time.

After his escape to the United States in 1939 he earns his living working as a graphic designer. From 1940 to 1945 he is the art director of various magazines: architecture periodicals such as Interiors and The New Pencil Points, both of which he helps open to the influence of European modernism; as well as fashion and culinary magazines such as You and American Cookery.

Later he also freelances for Harper’s Bazaar, Fortune and other periodicals, producing, among other things, a series of illustrated reportages on Italy immediately after the war. In 1952 he returns to Sardinia as a special reporter for Fortune to document, in a series of lively color illustrations published in 1953, the results of the antimalarial campaign launched by the Rockefeller Foundation.

In the garden of Long Island

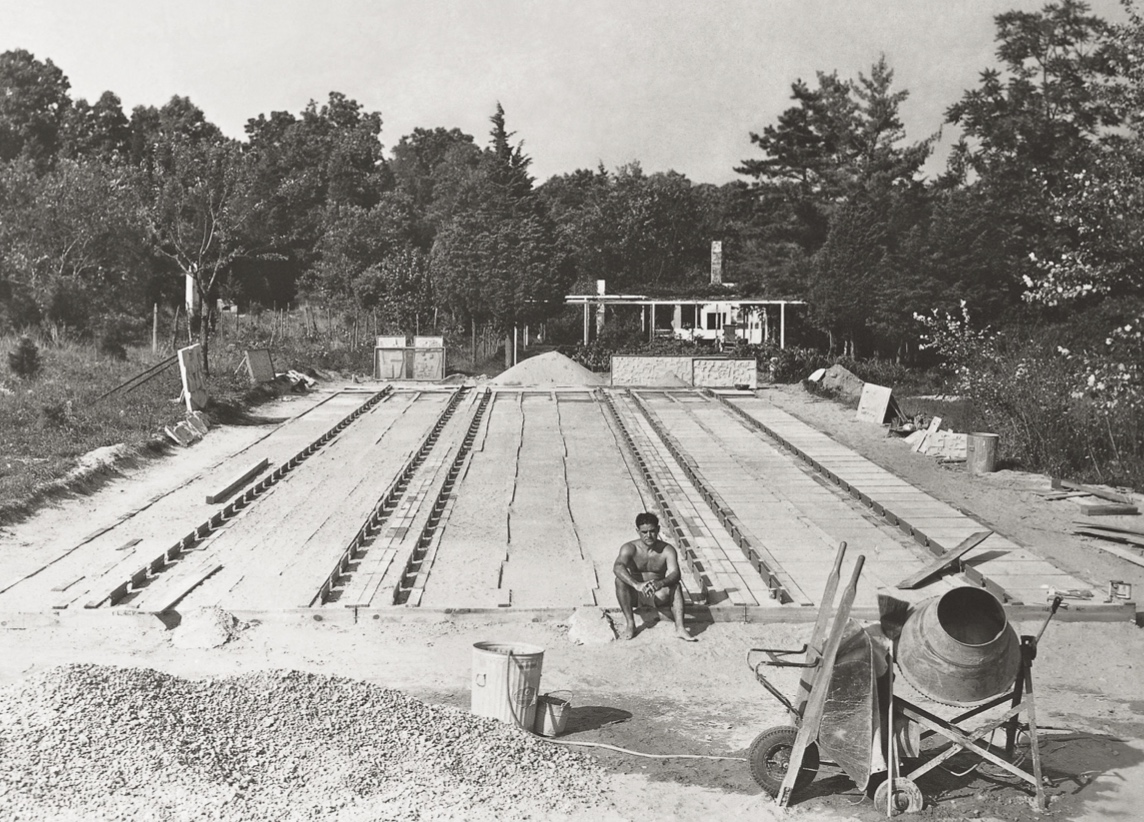

In 1948 Nivola purchases an old farm house on a parcel of land in Springs on Long Island, a vacation destination, very exclusive today but at that time still affordable and frequented by artists such as Pollock and Lee Krasner, De Kooning and Motherwell. Together with the architect Bernard Rudofsky, Nivola designs a garden in Springs envisioned as a series of openair rooms in which to live, work and entertain friends.

Furnished with pergolas and benches, a solarium, a fireplace and an oven, the garden soon becomes a creative laboratory. It is here, between 1949 and 1950, that Nivola becomes a sculptor, developing the sandcasting technique, a method, invented while playing with his children on the beach, of producing reliefs in cement or plaster from a matrix modeled in sand. And it is here that he produces his mural paintings and graffiti. Every year he adds, replaces or moves sculptures, erases and repaints murals. Aside from being a workplace, the garden is in itself a work of art, a work in progress, a never-ending exploration to which other artists also contribute – from Le Corbusier, who experiments with sandcasting, to Bruno Munari who leaves behind a mural, later painted over like all the other murals. The garden, however, is above all a place for socializing, a place to practice “the art of living”, where the aesthetic and the everyday merge together naturally.

A sculptor for architects

The success in 1954 of the Olivetti showroom relief earns Nivola a number of other commissions, launching him as “sculptor for architecture”.

At this time the international debate focused on the collaboration between visual arts and architecture, the so called “synthesis of the arts”. Modern architecture was perceived of as cold and distant; painting and sculpture could “humanize” and make it more accessible to the public. The sandcasting technique developed by Nivola was particularly suitable for this purpose. It enabled the making of relief panels mounted to cover vast surfaces – such as the façade of the Mutual of Hartford Insurance Company in Hartford, Connecticut, made in 1957-58, whose sketch is in the museum’s collection.

The sculptures were produced in concrete, the same material used in the construction of modernist buildings. The ordinary wooden frames in which the sculpted panels were cast were also used to pack and transport them by standard means of transportation to the site for installation, at the same insurance conditions than the building material.

Nivola aimed at a “normalization” of sculpture, stripping it of its aura of exceptionality and bringing it within the realm of everyday life. Works of art, he believed, once made part of communal life, should function to improve society by creating a more harmonious and pleasurable environment.

Nivola at work on the façade of the Mutual of Hartford Insurance Company, Springs, East Hampton, summer 1957

Art and Community

Growing up in the early twentieth century in a small Sardinian village, then transplanted to the metropolitan contexts of Milan and New York, Nivola looked back with nostalgia to a model of a united, cohesive and supportive society that the trajectory of modernization threatened to destroy. After World War II, Adriano Olivetti’s ideas of community as the prime nucleus of the democratic state, strengthen Nivola’s convictions. Further inspiration comes from the theories of Josep Lluís Sert. The Catalan architect, whom Nivola had befriended in New York and who had invited him to teach at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard in 1954, proposes a vision of urban planning founded on “civic centers,” places for citizens to come together.

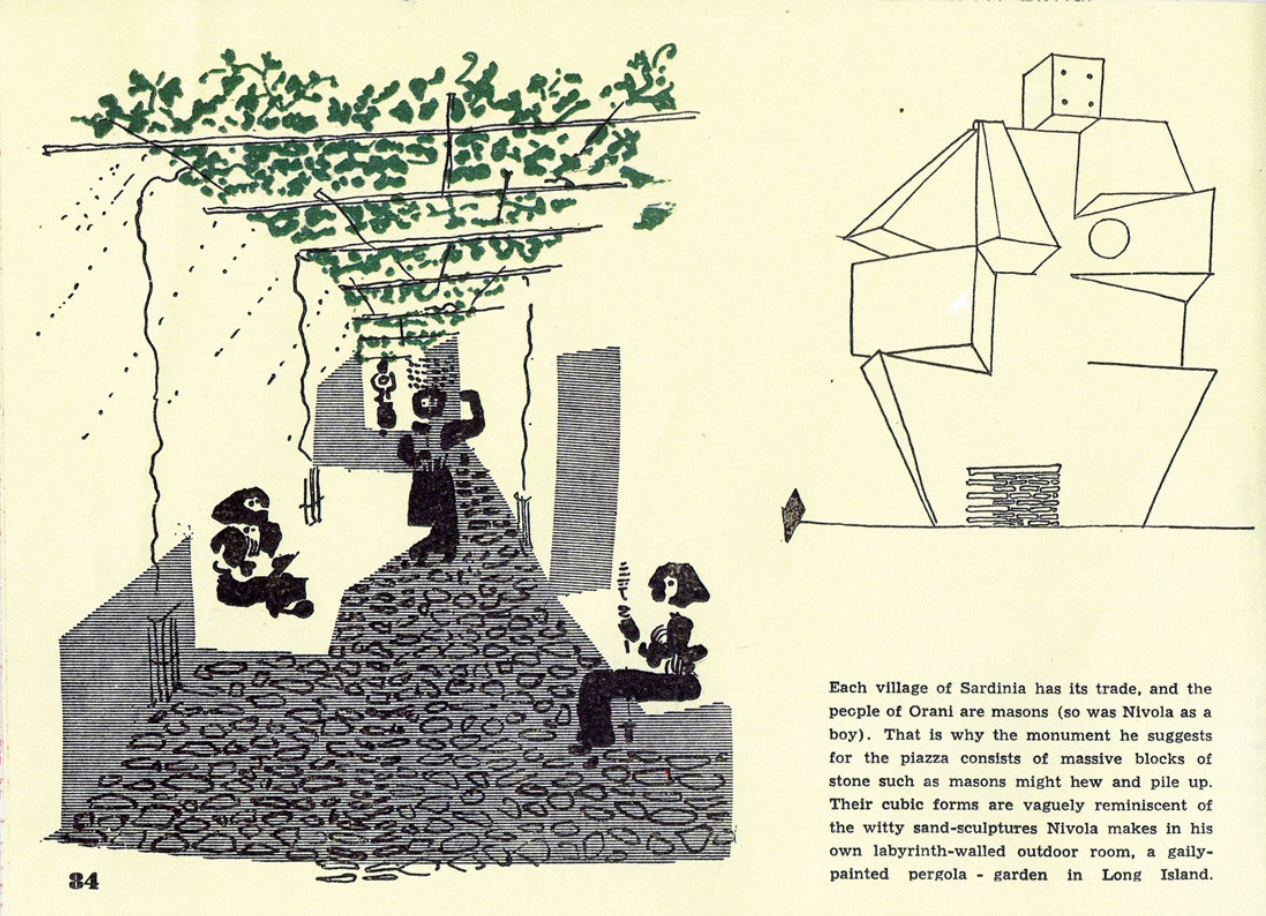

Starting from the Fifties, the themes of community life, participation and sharing gain importance in Nivola’s vision, resulting in profoundly innovative works such as the Pergola Village (1953), a project that sought to connect all the houses in Orani with pergolas, as well as a three-day exhibition in the streets of Orani in 1958, in which the involvement of the villagers was integral to the project itself. In these works the real focus, beyond sculpture and painting, is communal life, the social relationships between people: a vision that in some respects anticipates the trends of relational and participatory art of the 1990s and 2000s.

In 1953 Nivola publishes a series of drawings in Interiors illustrating the Pergola-Village project, conceived for his hometown of Orani. In the project, the houses are connected with one another by means of pergolas, turning the streets into intimate spaces to be enjoyed by all the inhabitants. The pergolas are a symbol that highlights and, in so doing, strengthens the social bond between individuals. Today, the modernity of his idea is striking: the artist goes beyond sculpture, painting and architecture, to explore the arena of daily life.

In his concept of transforming Orani into a “pergola-village”, Nivola envisions, at the center of the main square, a monument dedicated to the mason, a profession for which Orani is renowned, the trade of his father in which he himself has been trained. The unrealized project of the Monument to the Mason of Orani inaugurates the series entitled Building Blocks. Inspired by the principles of Cubist collage, these figures are composed of interlocking blocks of concrete. Nivola had visualized the Building Blocks as gigantic structures, “tall as buildings”, an achieved fusion between sculpture and architecture. Despite not managing to build them in the desired dimensions, the artist creates several models for the series.

In 1958, Nivola returns to Orani to build a tomb for his mother and brother. The memorial is composed of three sculpted plaques resting on short columns. Next to them, on metal poles, stand two small portraits: one of his mother holding bread dough, a symbol of nourishment and life; the other of his brother with mason’s jacket over his shoulder. The small dimension of the portraits originates from the desire to avoid any risk of rhetoric: “every human being, even the greatest, even the dearest, is after all a small thing. We should not turn them, with memory and sentiment, into an artifice of grandiosity”, Nivola said. Around the sculptures the artist plants wheat, instructing that, once grown and cut, it should remain there as part of the monument, a possible reference to the pagan idea of death and resurrection.

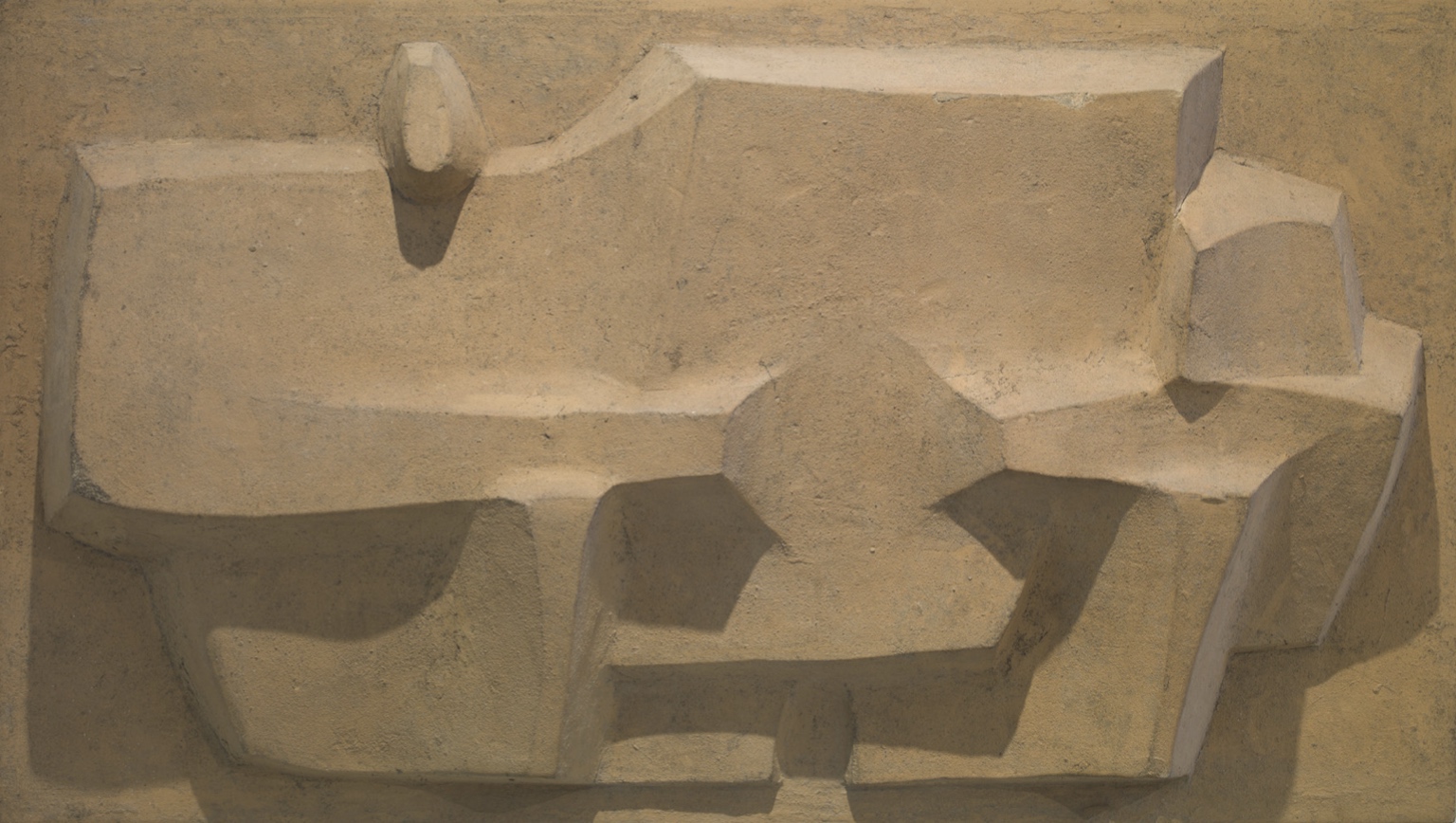

Model for the Monument to the mason of Orani (from the Building Blocks series), 1955, concrete, cm 63,5 x 68,5 x 34, 5.

Photo P. Pinna

At Yale

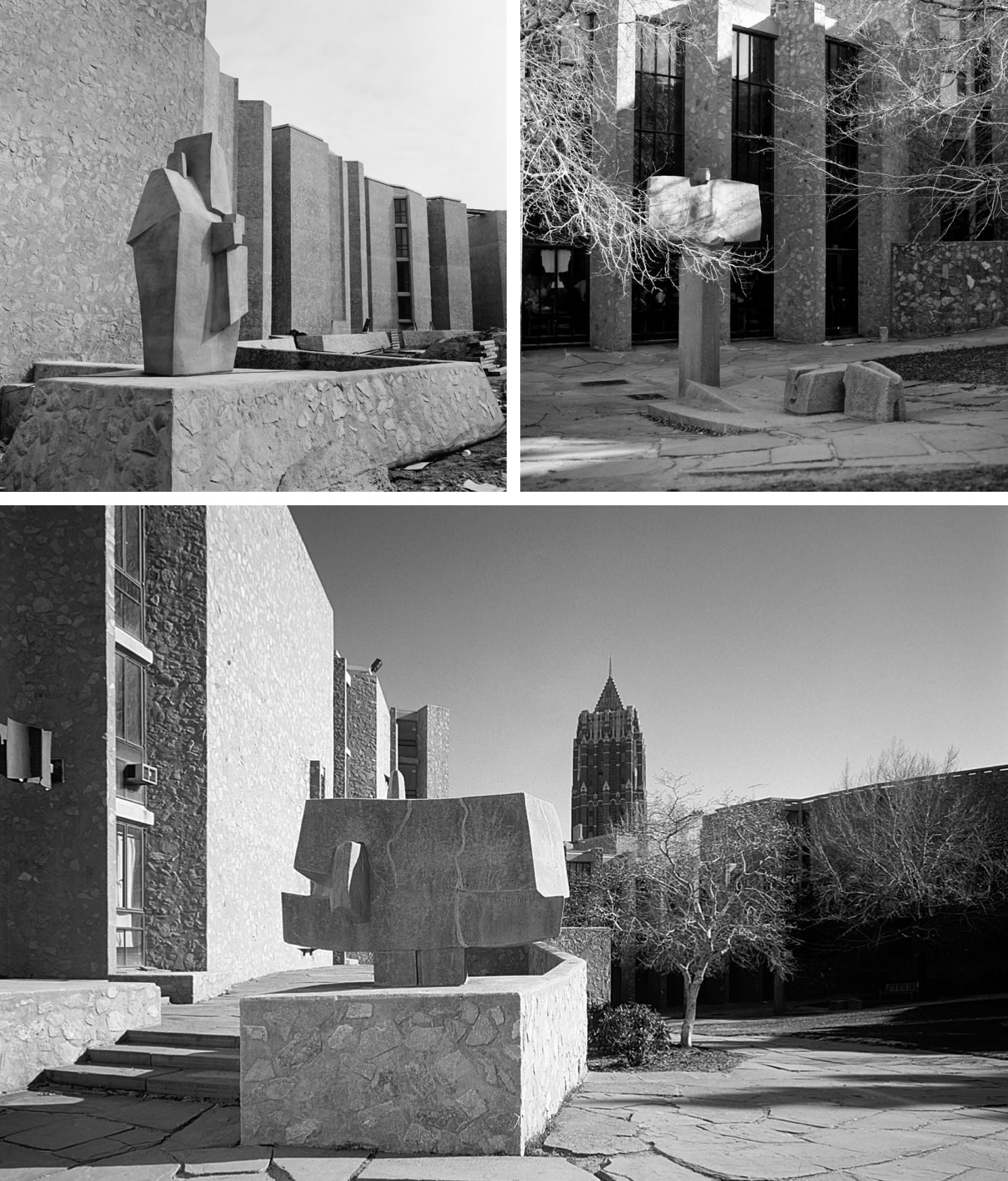

The decoration of the Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges at Yale University is perhaps Nivola’s most successful example of the dialogue between sculpture and built environment.

In 1959 Eero Saarinen – at that time the most celebrated architect of his generation in America – writes to the artist asking him to work on the project for the colleges. Saarinen, who was inspired by San Gimignano and the Medieval towns of Italy, does not ask Nivola for an individual sculpture or simple wall decoration, but rather a “whole atmosphere created by sculpture and relief in relation to the architecture”. Nivola accepts the challenge and produces 43 works: three-dimensional sculptures, reliefs and fountains carved from blocks of semi-solid concrete (his technique of cement-carving).

The work is completed in 1962, one year after the death of the architect. Appearing at various heights throughout the campus the sculptures, some large and solemn, other small and subtle, form a visual itinerary full of surprises and unexpected perspectives. Made of concrete like the buildings, the art work blends in harmoniously and accompanies the visitor without imposing its presence on his attention. Nivola comes close here to realizing his dream of a full integration between art and architecture.

Views of the Morse & Stiles colleges, Yale University, New Haven (Connecticut), architect Eero Saarinen, 1959-1962

The Sixties and the Seventies

In these years Nivola completes numerous projects and consolidates his reputation as “sculptor for architecture” (such that, in 1963, he is asked to be part of the team in charge of the rescue of the Abu Simbel temple in Egypt).

Perfecting three techniques (sandcasting, cement-carving and graffito), employed individually or in combination, Nivola participates in the design of private and public buildings, as well as urban areas in New York and in the rest of the United States. Sculptures and bas-reliefs are also presented as autonomous works in museums and art galleries.

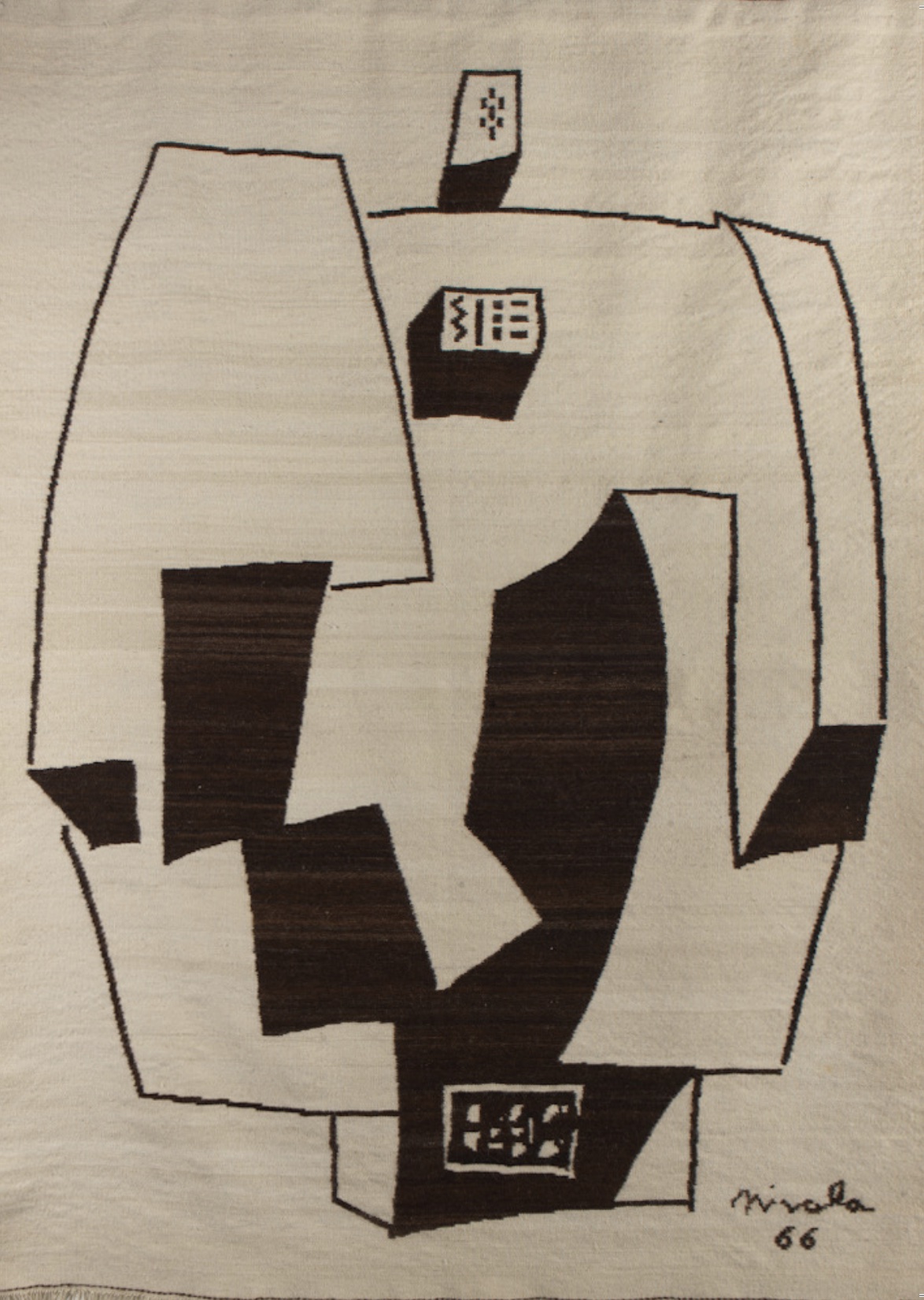

The human figure – a constant point of reference for the artist – is subjected to a process of simplification in form. Two typologies of sculpture clearly emerge: one characterized by gentle, enveloping lines and another by geometrical shapes, squared and precise. Lines in relief and traces of seashells and other sand impurities gradually disappear. Surfaces become smoother and more regular. The links with Italy increase: in Sardinia he commissions woolen tapestries, in Tuscany he visits the quarries of Versilia. At the beginning of the Seventies, Nivola starts to use marble and bronze for his large scale sculptures, materials that will become characteristic of the last phase of his work.

Crime and the Law, model for a sculpture at the Bronx Family and Criminal Court, 1963-1967, concrete, cm 74,8×52,5×32,5. Architects Harrison & Abramoviz.

Photo P. Pinna

Painting / Sculpture

In the Seventies, Nivola resumes easel painting: a way of thinking about space and reflecting on the relationship between the flat surface and the three dimensional image.

A series of large geometrical figures is characterized by warm and subdued tones, in fashion in the Seventies, and by the ambiguity between subject and background: the volume of the figures is alternately negated or emphasized by the application of color passing from one plane to another.

Here too the interest of the artist is on the definition and perception of space.

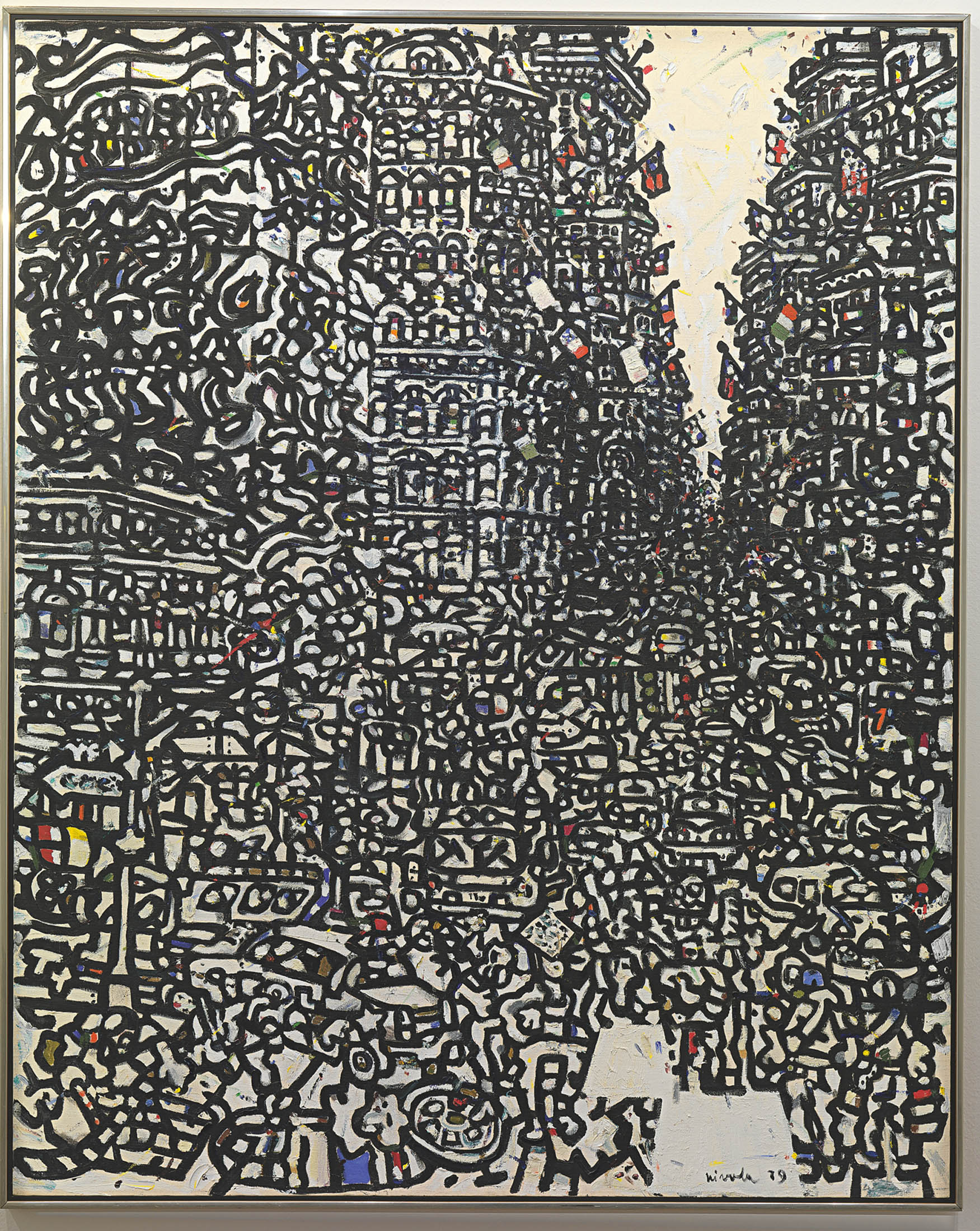

In another series, Nivola returns to the same views of New York that he had painted in the Forties, but with a different style: deeper blacks, less defined contours and a darker atmosphere, marking a more critical and mature look at the “marvelous city” that had welcomed him at his arrival in the United States.

The return to painting is part of the same process of redirection to “pure” art that guides Nivola’s relationship with sculpture in this same period.

Thinking the space

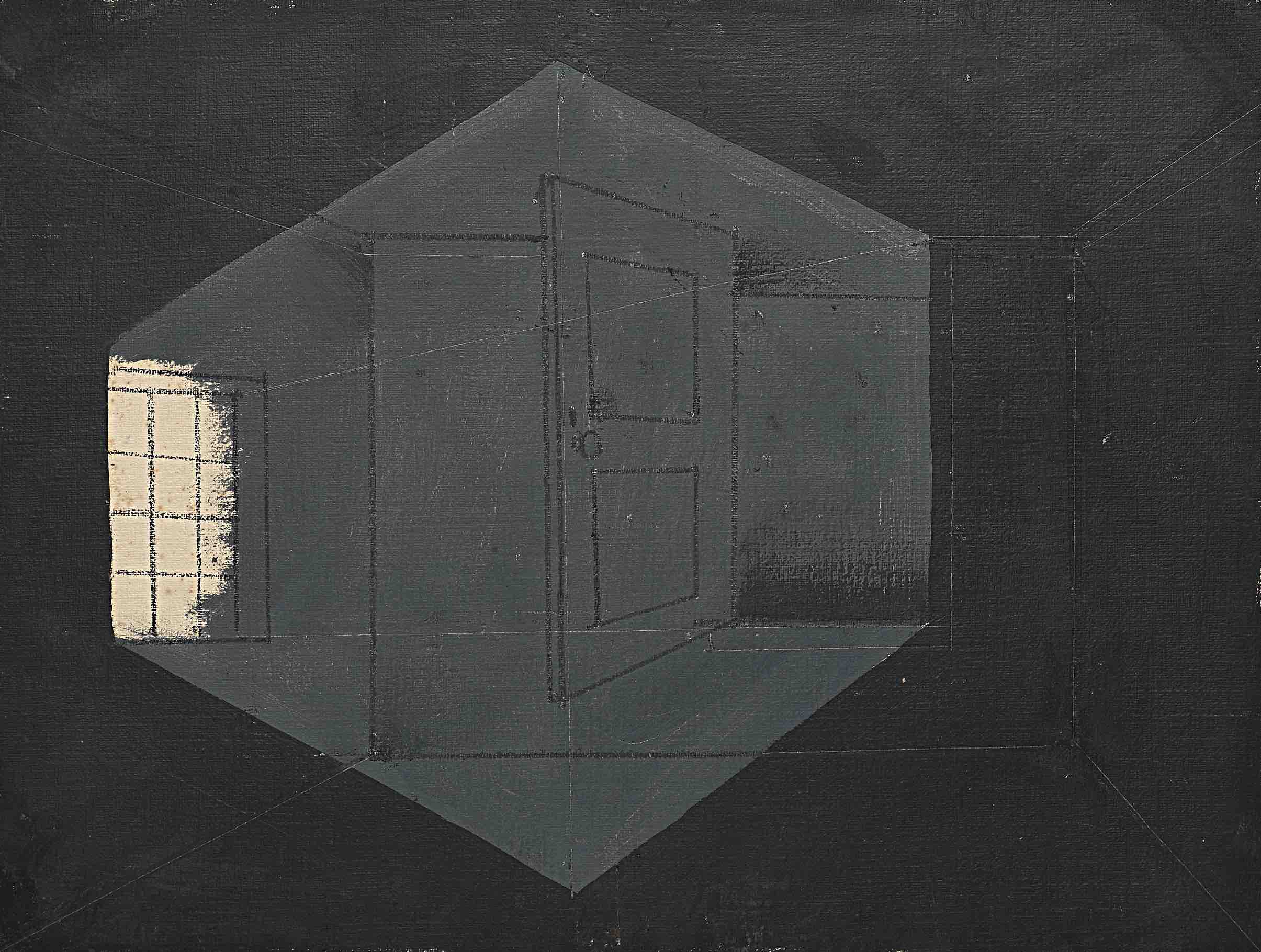

The exploration of space, constant in Nivola’s art, leads him in the Seventies to elaborate the theme of “rooms” in drawings, paintings and sculptures. Actual works of art rather than architectural sketches, the rooms reinterpret the idea of space, shifting it from the public arena (as in the Antonio Gramsci memorial) to a private and existential sphere. Simple geometrical forms, open on the front side, the rooms have small windows to let in the daylight that in turn modifies the space. In a poem titled “Omaggio a Marcel Proust” (Homage to Marcel Proust), Nivola sums up the meaning of the rooms:

Inside this room I shall find

what I have

Always searched for, all variants of the

Square and

of the cube. The infinite linear variations

Of

The vertical and horizontal.

In all the degrees of the angle I shall

Find

Myself as sole organic form. In this

Temple

Of Cartesian structures suspended in the

Chaotic context

Of infinite rifts.

Room of the pregnant wall, first half of the ‘80s, styrofoam and plaster, cm 24 x 31,3 x 32. Photo P. Pinna

Microcosm / Macrocosm

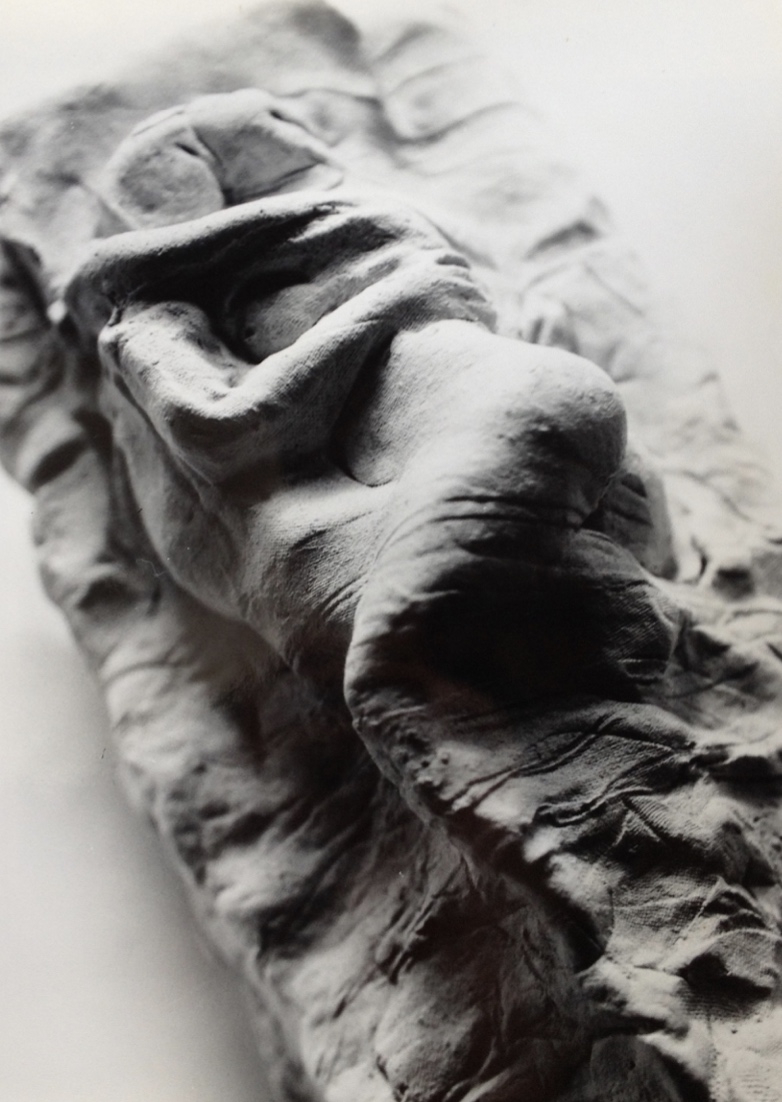

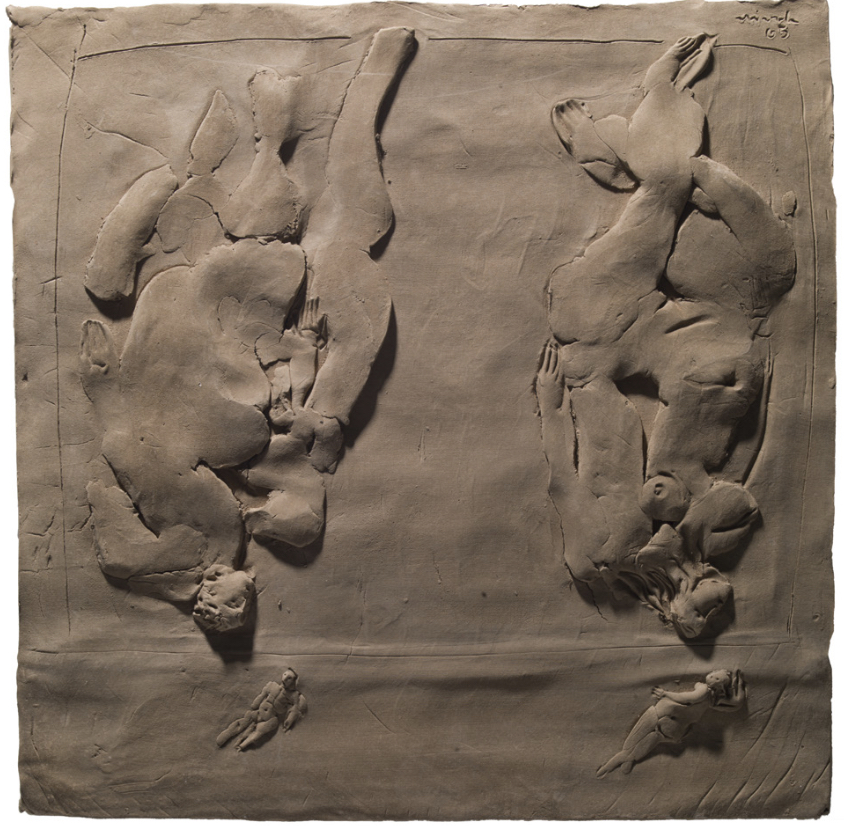

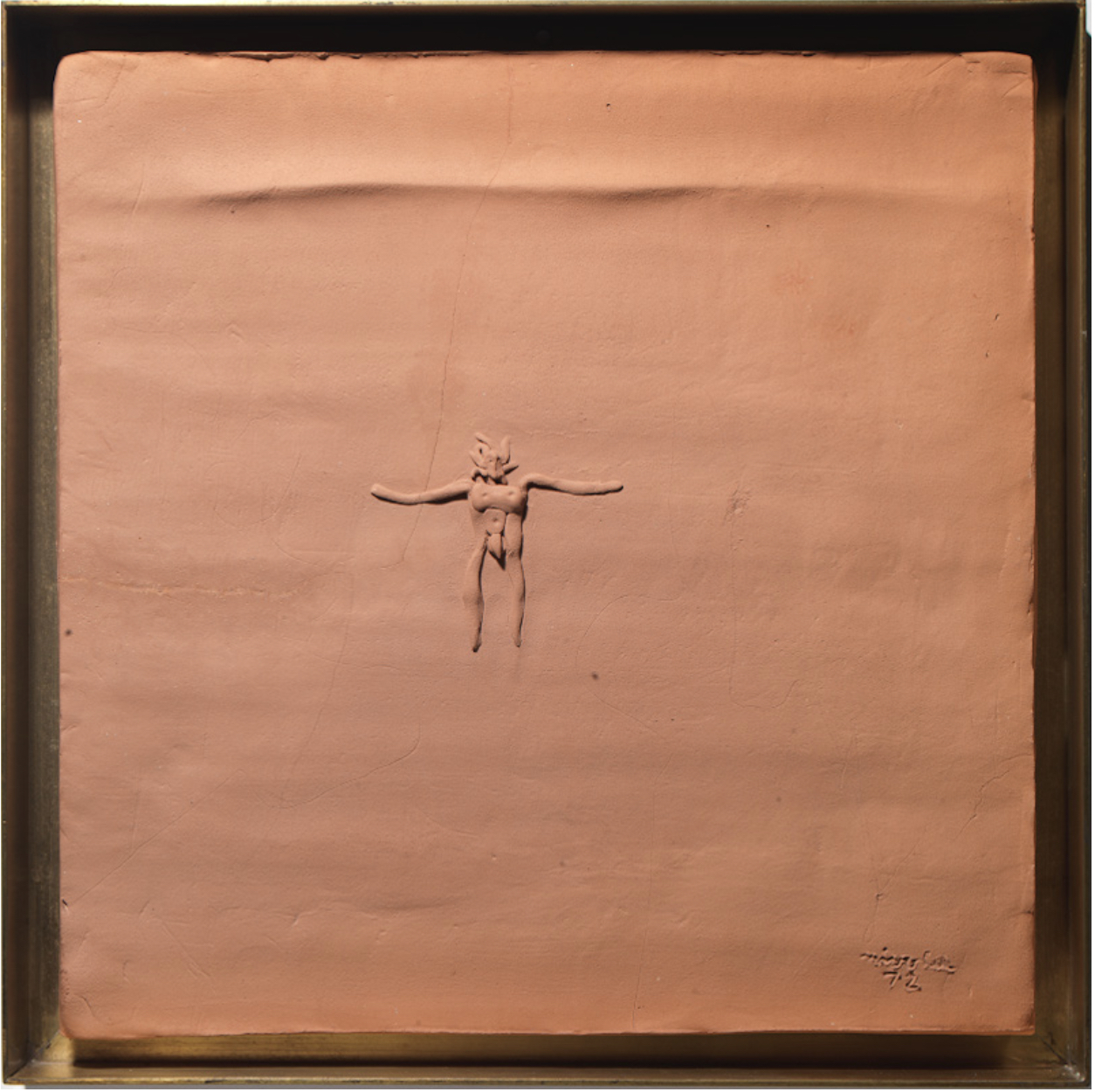

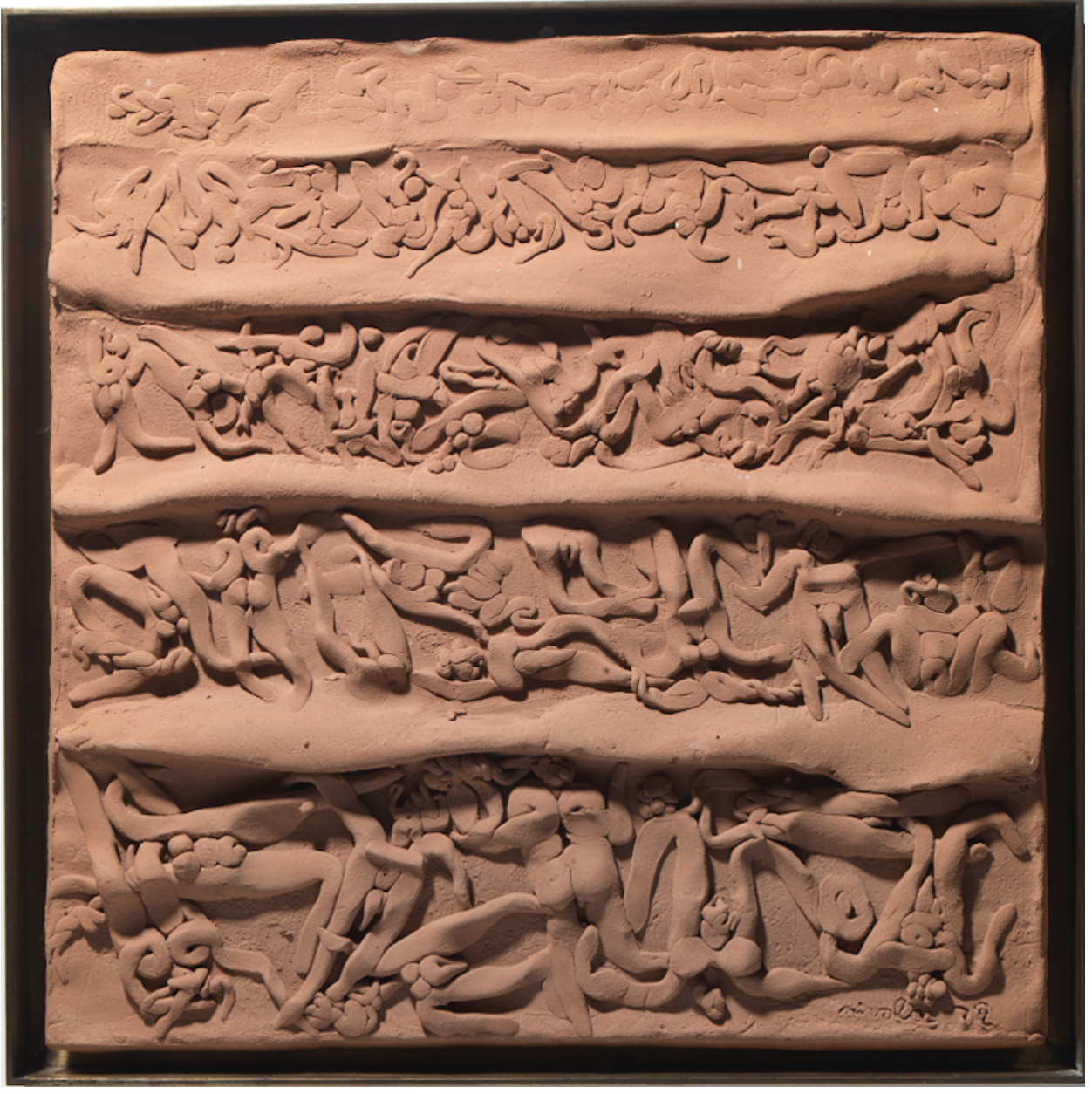

At the beginning of the Sixties Nivola starts to use clay for small-format pieces, enjoyed as completely free forms of expression, an alternative to the rigors of public works subjected to the whims of clients and the requirements of architecture.

The Beds, inspired by Etruscan sarcophagi, embrace by extension the totality of human existence: conjugal life in all its variants, moments of solitude, happiness and despair. Nivola places them on white bases, imbedding them in sprouting grain, a symbol of rebirth traditionally used in Sardinia during the rites of the Holy Week. From the microcosm of the Beds, Nivola moves with the Beaches to the macrocosm of nature. He delineates swiftly marine landscapes in which small figures rest on a beach or swim towards the horizon. In the series Gods and Humans, clouds take the shape of pagan deities that watch over unaware mortals below.

In the Seventies, Nivola, disillusioned and critical of contemporary society, produces new beds and beaches, humorous and sarcastic, often explicitly sexual, and creates the series Swimming Pools, sites of urban amusement in which bodies amass and every relationship with nature is negated or distorted.

Bed from the series The Embraces, from the flyer of the exhibition Nivola. Divertimenti, Galleria dell’Ariete, Milano, 1962.

Photo Robert Galbraith.

The Great Mother

“For some time, in my sculpture emerges a simple, essential force. Here spirit and senses collaborate in giving shape and meaning to matter. There is a female form as a result, but not necessarily as a starting point. The potbellied wall of a rustic house, in my magical childhood, always hid a treasure: the flat and thin bread that swells with the oven heat, the promise of satisfying an everlasting hunger.

At the same time, the pregnant woman hides in her womb the secret of a wonderful child.”

This is how Nivola explains the meaning of the Great Mothers – icons of his later work.

Already at the beginning of the Seventies, Nivola develops what he defines as “a hunger for marble and bronze”, the desire to use sculpture’s “noble” materials to get closer to a “pure” art, independent from architecture.

Imagined monuments

After the Second World War, the monument as artistic form is regarded with suspicion because of its associations with totalitarian regimes. The statue of the leader in the middle of the city square is rejected as rhetorical and false. The proposals of artists and intellectuals such as the Spanish architect Josep Lluís Sert – linked to Nivola by friendship and by a professional relationship – rethink monuments as possible fulcrums of new city centers, designed on an environmental scale, employing architecture and sculpture to create experiences of visual wonder for a better daily use of city spaces. Public art is for Nivola primarily a matter of civic responsibility, a simple and concrete way of improving people’s lives. He writes: “If artists and architects fail to meet the challenge of making cities more beautiful, others, less equipped with imagination, and groups lacking civic responsibility will continue to perpetuate the architectural evils of our cities.” In the years of maturity, however, the sculptor begins to favor the utopian and visionary dimension of the monument. Some of his projects will never come to life because of external circumstances, others, born as works of imagination, remain valid regardless of their chances of being realized.

“With time,” says the artist, ”I learned to appreciate the utopian quality of imagination, almost preferring it to actual realization, which always involves some inevitable disillusion”.

At the end of 1963, Nivola is asked to design a square in Nuoro, dedicated to the early-twentieth century poet Sebastiano Satta. This will be the first public artwork by Nivola in Sardinia (another would be his commission for the seat of the Sardinian Regional Council in Cagliari twenty years later). The artist does not just design a traditional monument; with his friend, the architect Richard Stein, he reworks elements of the entire space, including its park benches, the white walls and blue skirting board of the surrounding houses, and the type of pavement. Instead of a central monument, Nivola situates large boulders in various parts of the square. He places small bronzes in niches. These show the poet in his daily activities. Nivola envisioned Piazza Satta as a communal living space in which to walk and pass time, as well as a memorial wherein to reflect.

In 1968 Nivola starts working on a monument to Antonio Gramsci to be built in Ales, Sardinia, home village of this famous political theorist. Nivola regarded Gramsci as the “greatest of the Sardinians”: one who overcame humble origins and acute physical disabilities to become an intellectual of historic importance.

The monument, designed with Richard Stein, evokes the Fascist jail where Gramsci was imprisoned, and also the room where, in his childhood, his mother would suspend him in the air in a misguided attempt to correct his disability. The door, only 1.55 cm tall, encourages the visitor to lower his or her head in a gesture of respect. The absence of a roof represents the ability of Gramsci’s thought to reach far and wide, in contrast to the sense of restriction conveyed by the two bronze portraits of Gramsci as a child and as a prisoner. According to Nivola, who felt spiritually close to Gramsci, the monument is not a simple commemoration but an occasion to meditate on the thought and life of the philosopher of Ales.

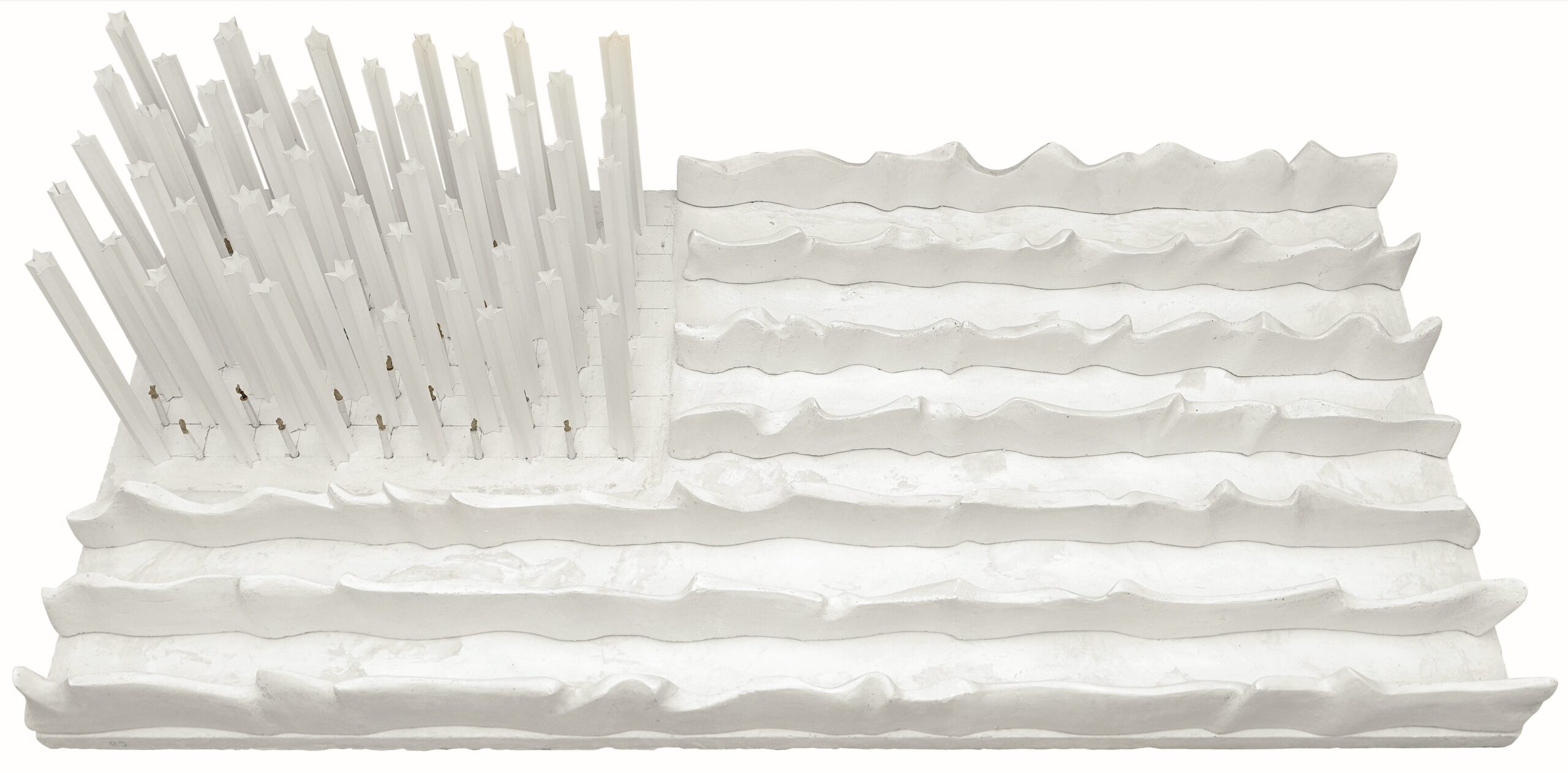

In 1960, in occasion of the competition for a memorial dedicated to Roosevelt in Washington D.C., Nivola reflects on the form and meaning of the American flag, at that time a recurring element in the works of New Dada and Pop artists. Translated in three-dimensional forms and in monumental scale, it would have become a livable space similar to the one envisioned for the monument to the “Sassari” Brigade. The stripes are curving walls, as if moved by the wind, creating corridors through which visitors would walk, flowing as if in a “land of opportunity”, toward a cluster of tall columns—the stars of the fifty states. Towering columns, in a geometric vertical group, form an interesting juxtaposition with the waving horizontal alleys (the stripes).

In the Eighties, inspired by the period he had spent in Washington as a juror in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial competition, Nivola returns to the FDR project, now imagining it built in marble, and widening the scope of its content with a collection of small statutes of various other illustrious figures in American history interspersed between the pillars of stars. The anarchic spirit of Nivola and his awareness of the contradictions of consumerist society do not prevent the artist from picturing himself as one of the many migrants who had lived the “American dream”. Beginning circa 1974, Nivola returns to making a series of paintings that revisit American cityscapes, especially of New York. (His earlier versions had been in the 1940s.) They capture at once the magical vitality but also the edgy, chaotic qualities of the city. “I am determined – he writes – to put everything I know about the subject, the art of painting and the discipline of seeing in a series of paintings. It will be hard work, not a joyous task but a somber, objective and truthful approach to a realistic and merciless city”. Vehicles, pedestrians, the old bricks buildings, the imposing skyscrapers of glass and steel – all this and more is fused in an urban scene that is at once recognizable and abstract.